Paris, rue de Grenelle St. Germain 65

4th january 1862.

My dear Sir,

I shall have the pleasure to send you in a few days my explanation of the Borsippa text of which I have found a separate Copy, and I am most happy to continue at that occasion the epistolar intercourse with you. You tell me in your kind letter, that you are quite satisfied with the letter answer to M. Schoebel,<1>

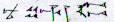

I shall now reply to some other questions of your kind letter: first, to your opinion of on the grammatical laxity of the Assyrian language. Of course, you have in the great number of forms, from Hammurabi’s phonetical text to Selenous and Demetrius’, some words that are not quite identically written: but if you recollect the thousand years’ distance, you will difficultly find a language where in which the changements were less considerable than in the Assyrian tongue. you will find some difference between Ninive and Babylon, but this discrepancy is rather a lexical one. You have no other laxity in the language than that which resulted from the very Suranic scripture, and from the syllabical conplexion of the anarian character. But that is all, we can possibly admit and [ill. del.] these variations do not attain the laxity of the present arabic language. If we have, for instance

ra- sar [hebrew], the infinitive, we cannot identify it with

ra- sar [hebrew], the infinitive, we cannot identify it with

na-sir, [hebrew], the participle, as, in the paël voice, we cannot confound

na-sir, [hebrew], the participle, as, in the paël voice, we cannot confound

nussur (inf.) with

nussur (inf.) with

nussir [hebrew] (imperat.). Hammurabi says askun, I made, like Nabonidus, and if Assarhaddon will distinguishes astur, I wrote, from sutur write, (imp.)

nussir [hebrew] (imperat.). Hammurabi says askun, I made, like Nabonidus, and if Assarhaddon will distinguishes astur, I wrote, from sutur write, (imp.)

You will not accept dear Sir, the non-identity of

and ammat. I know the passages [ill.del.] you allude to: I have published them, with the text and an explanation, two years ago, I am aware of all the difficulties of the Nabchodonosor inscription, and I have explored myself the ground of Babylon,

and ammat. I know the passages [ill.del.] you allude to: I have published them, with the text and an explanation, two years ago, I am aware of all the difficulties of the Nabchodonosor inscription, and I have explored myself the ground of Babylon, whose the site I now describe in the publication almost finished of the Expedition of Mesopotamia. But why in the ten values of

the tablet does not give that of anmat? You say yuzakkir, is not from לכז. Why

the tablet does not give that of anmat? You say yuzakkir, is not from לכז. Why write do you write yuzakkir if you translate I built? You quote the well known passage risisa uzakkir sa hursanis, you explain by “I built it handsomly.” But what is your authority for translating handsomely a word derived from סלח to engrave. Now Still now, a cylinder is name khirsch in Mesoptamia; and I translate, “I commemorated its beginning on cylinders.” And even, if I should concede for a moment that uzakkir had another explication, where is your authority for interpreting

by ammat? While I have a Direct, [ill. del.] jusfication of its being explained by amar. And hursamir is evidently, and adverb formed from a plural like tilanis, sadanis, sandanis, abubanis, aranis. If you

by ammat? While I have a Direct, [ill. del.] jusfication of its being explained by amar. And hursamir is evidently, and adverb formed from a plural like tilanis, sadanis, sandanis, abubanis, aranis. If you had expected a simple adverb formed from an adjective, you would have hur’sis, like rabis, namrir, naklis, nagaris, sakis and others. There is existing a verb whose paël may be written uzakkir or usakkir, and which may have the sense of build; but the verb לכז has also at great number deal of probability and I should find easily in your very interpretations many instances permitting to explain the passage: “they built it 42 ages ago.”

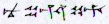

You refute me also, dear Sir, on the ח hebrew, and its elimination in assyrian. I have no instance for the changement you note. I should bye glad to see the number one represented by the Chaldae [character], and written at. The only passages where the unity occurs gave these following form.

In the two instances you have the number

with the phonetic complements, as you have

with the phonetic complements, as you have

sanu two and

sanu two and

salsi three. The

salsi three. The for masculine form is from [hebrew], in hebrew [hebrew], and the second the hebrew feminine [hebrew]. The [character] has been observed in the [hebrew] form, and the [hebrew] form has not this articulation, and is a distinct expressn for the unity, as you may quote in the indo-european languages the radicals aiva, mon, and mi.

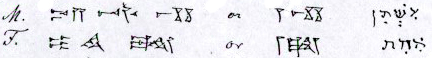

The god I name Nisroch is

;the identification seems to be very probable [hebrew]

;the identification seems to be very probable [hebrew] the, because

The god I name Nisroch is

has the power nis, and

has the power nis, and

the value nek. Nisroch, you know is the god Hymen, and the name is from [hebrew] to bind together, But this is only a highly plausible hypothisis. On the other side, the identification with Salman is no personal opinion, but proved by the inscriptions. You have

the value nek. Nisroch, you know is the god Hymen, and the name is from [hebrew] to bind together, But this is only a highly plausible hypothisis. On the other side, the identification with Salman is no personal opinion, but proved by the inscriptions. You have

, and you [ill. del.] are aware from numerous text, that

, and you [ill. del.] are aware from numerous text, that

has the signification of Salam; you find or ta.

has the signification of Salam; you find or ta.

. samas, or with the phonetical complement ta.

. samas, or with the phonetical complement ta.

mu. samas, or ultu salmu samas.

mu. samas, or ultu salmu samas. Yo In other instances there is to be found with the same compliment

ma nu and this god has since long been said Salman. In the Sardanapalus inscription (pl.23 l.135) you have

ma nu and this god has since long been said Salman. In the Sardanapalus inscription (pl.23 l.135) you have

mannu, and this complement does not admit an other identification than that of Salmannu, as

mannu, and this complement does not admit an other identification than that of Salmannu, as

is Istar, and the tar is even Superfluous, for us. If we had many [illegible] indications, as this, we knew more about the Pantheon of the ancient Assyrians. We have thus

is Istar, and the tar is even Superfluous, for us. If we had many [illegible] indications, as this, we knew more about the Pantheon of the ancient Assyrians. We have thus

, Zarpanit,

, Zarpanit,

Nergal (there

Nergal (there

is doubtful in the phonetical exception). This

is doubtful in the phonetical exception). This latter god is named

il halik paniya[?], thus explained by the Syllabaries, and confirmed by the commencement of the Sardanapalus from back, l.2 pl.27. You have many instances for two names, as Ninip and Sandan [hebrew], Sandan of the Greek, Belus and Dagon and other.

il halik paniya[?], thus explained by the Syllabaries, and confirmed by the commencement of the Sardanapalus from back, l.2 pl.27. You have many instances for two names, as Ninip and Sandan [hebrew], Sandan of the Greek, Belus and Dagon and other.

Excuse, dear Sir, the length of this letter, but you know, there are few assyriologists in the world, and they better work together and help look for inspiration coming from abroad, that to write each against his their competitors; and therefore I like much more, to expose to yourself and to your kind appreciation the few objections I can find, than to publish them, and I shall be anxious, to entertain listen to your views and to profit by them.

Believe me yours most truly

J. Oppert

[envelope:]

H. Fox Talbot Esq.

Millburn Tower

Edinburgh <2>

Notes:

1. Charles Schoebel (1813-1888), "Examen critique du dechiffrement des inscriptions cuneiformes assyriennes," Revue orientale et americaine, v. 5, 1861, pp. 174-220.

2. Millburn Tower, Gogar, just west of Edinburgh; the Talbot family made it their northern home from June 1861 to November 1863. It is particularly important because WHFT conducted many of his photoglyphic engraving experiments there. The house had a rich history. Built for Sir Robert Liston (1742-1836), an 1805 design by Benjamin Latrobe for a round building was contemplated but in 1806 a small house was built to the design of William Atkinson (1773-1839), best known for Sir Walter Scott’s Abbotsford. The distinctive Gothic exterior was raised in 1815 and an additional extension built in 1821. Liston had been ambassador to the United States and maintained a warm Anglo-American relationship in the years 1796-1800. His wife, the botanist Henrietta Liston, née Marchant (1751-1828) designed a lavish American garden, sadly largely gone by the time the Talbots rented the house .